A production and a performance may to a greater or lesser extent affect us like a dream. But every production has one thing in common with a dream. No one dreams yesterday’s dream: the essence of dreaming, whether by day or by night, is of the moment, images fusing from past and present in a new apprehension.

(Mudford, 2000, 23)

As Mudford states, no one dreams to replicate exactly what has already been achieved. Sure, a company can take elements of previous successes and look at adapting these into new and original projects, but companies must always be aiming to be innovative and provide something novel, however small, to the theatrical world. Mudford’s ideas of fusing the past and the present to form something new is particularly resonant with the way Refract are working. Whilst experimenting primarily with many different famous images, this is simply only the first piece of an unfinished puzzle.

It’s about layering preexisting theatrical elements in new ways.

Building up new and non-conventional combinations of everyday theatrical devices, such as music, projection, text, movement, live feed etc, allows the audience a fresh look at the matter being presented to them. Many productions begin with a pre-written script that acts as a basis, with other devices being considered later on in the process. However, in a similar way to how Tim Etchells, director of theatre company Forced Entertainment, describes his writing as simply becoming “part of the messy group process” (Billingham, 2007, 165), we are also working in a way that allows aspects other than script to become the foundations of a scene. Forced Entertainment devise in such an unstructured manner that written text would only linearize the process and limit the various directions that the work could take. For Etchells, the word ‘text’ has become something else. Forced Entertainment “have come to work with improvised text and speech [presenting] a shift in the work from an interest in writing to an interest in spoken language” (Giannachi et al, 2012, 189) This shift has meant that text has been transformed into other devices of communication, instead transforming ‘texts’ into different ‘textures’ within performance.

Text is used only when appropriate.

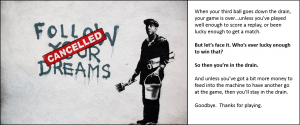

Being a company that uses image as it’s springboard to creativity, this often leads to the actors improvising with their bodies first and foremost. In a rehearsal inspired by street artist Banksy, I had pre-selected a series of his various artworks to use within rehearsal. Separately, I had written 5 pieces of short text and selected a playlist of around 8 songs, some lyrical, some instrumental, to use also. The actors were instructed to simply follow my every improvised command for the next 45 minutes.

Directing actors around the space I find is a little bit like conducting an orchestra. You need something gentle to kick start the action, or music. In this Banksy rehearsal, it was a series of easy physical instructions. Then as your orchestra begin to warm up, you add in more and more people, and maybe another layer of meaning to ensure the audience that the company still have more to offer, for example, the introduction of a piece of music. A steadily increasing shift in tempo begins to build up the on-stage image and suddenly you begin to see the full cast functioning as an ensemble, or an orchestra, instead of individuals. It was at this point, as the action was occurring on stage, that I then deprived them once again of that ensemble-feeling. This time, by giving one individual a set of different instructions and some text to read out. Everything that had happened previously was then linked directly to this piece of text; a new instrument was added that was unexpectedly louder than the others. Once the text had been read out, the movement felt emptier. Then, like the end of an orchestral piece, I began to find some harmonious way of rounding-off the workshop. It eventually finished by winding down the high-speed movement, drawing out cast members one-by-one to return to their seats offstage, leaving one sole person at the end with one final piece of text.

Constantly shouting new instructions and gaining an instant response on stage allowed me to envisage exactly where the workshop was heading. In a discussion afterwards we all agreed that we loved the use of attaching seemingly unrelated pieces of text, for example one was about the workings of a pinball machine, to the movement on stage, and how it challenges the audiences to dig deeper into how the text and movement are related. (see image 1)

Suddenly, it isn’t a pinball machine anymore, its life. You’re the small metallic ball, making its way as successfully as possible down the table with various obstacles and distractions along the way, only to end up in the same place you started.

Refract will be continuing to adopt this layering process of theatre-making, introducing a live video recording and experimenting with live music.

Works Cited

Mudford, P. (2000) Making Theatre: From Text to Performance. London: The Athlone Press.

Billingham, P. (2007) At the Sharp End. London: Methuen Drama.

Giannachi, G., Kaye, N. and Shanks, M. (2012) Archaeologies of Presence. Oxon: Routledge.

Stencilrevolution (2015) Follow Your Dreamsn Cancelled by Banksy. [online] Available from

http://www.stencilrevolution.com/banksy-art-prints/follow-your-dreams/ [Accessed 20 March 2015].