Months and months equating to hundreds of hours’ worth of rehearsals, meetings and research was finally made worthwhile on Sunday night when Refract Theatre Company performed our debut piece, When You See It at the Lincoln Performing Arts Centre.

For the first time ever, I was able to sit back as an audience member and watch the show take place without the need to scribble down notes or constantly be thinking things through from a director’s point of view. Of course, these things were hard to escape, especially when unexpected mishaps happened on stage that hadn’t before, as is the way with any live performance. For this, I am grateful that I adopted Theatre Workshop Director Joan Littlewood’s ambition of wanting “actors who were equal partners with her in the creative process, who could explore possibilities in rehearsal and be able to adapt to change, respond to interruptions from the audience and cope if someone in the company messed up during performance.” (Holdsworth, 2006, 48). Overall, I was confident that the actors were rehearsed enough to problem solve any unexpected occurrences on stage, and it was a pleasure to be able to just enjoy the show that was existing in front of me.

As a company, we have stayed true to the original intentions stated in our manifesto. Storytelling is still just as important to us as it was from day one, and watching audience members laugh, cry, be both haunted and comforted by the love story of Billy and Dolly meant that we had ultimately achieved our goal of taking them on a journey. A particularly poignant moment was when a long moment of quietness occurred as Billy comes to the realisation that Dolly has died (See image 1). Within quite a sound-heavy show, the sudden change in pace and style could have easily disengaged the audience had the story not been gripping enough to carry them through the more reflective moments. As Mudford notes, “the silence in the theatre when ‘you hear a pin drop’ is caused by the intensity with which that act of imagination continues; the audience is quite literally in a state of suspended animation” (2000, 47). There was a genuine interest in the two characters.

Image 1 – Lone Billy. (Lincoln School of Fine and Performing Arts, 2015)

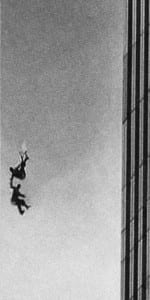

Unknowingly, towards the end of the process, the production had adopted one image in particular as it’s ‘mascot’ image. An interpretation of the two people shown in image 2 occurred during almost every scene, becoming a symbol of love, relationships, and also of life and death.

After discussing the image in detail by itself, assuming no previous knowledge, we came to realise that there are two ways it could’ve been interpreted; the people were either falling, or they were flying.

When You See It was a show that explored the personal, through Billy and Dolly, sandwiched in between large-scale universal images and events. It played with chance, coincidence and fate.

We have received excellent feedback for the show from lecturers, fellow drama students and local theatregoers of all ages, and are positive that, should the production be toured in the near future, it would be easily adaptable to any venue and appeal to a wide range of people.

Works Cited

Holdsworth, N. (2006) Joan Littlewood. Oxon: Routledge.

Lincoln School of Fine and Performing Arts. (2015) Refract. [online] Available from https://www.flickr.com/photos/61839232@N02/sets/72157653037257285. [Accessed 18 May 2015]

Mudford, P. (2000) Making Theatre: From Text to Performance. London: The Athlone Press.